As consumers Americans have come to expect an incredible variety of choices… And we’ve got them. Every day we are faced with increasing numbers of choices:

- Which of the thousands of cable channels do you watch?

- How do you like your coffee? What drive-through do you get it from?

- Do you cook for yourself or choose to become a valued customer at Mighty Taco

Then there are the more involved decisions like who we add as ‘friends’ on Facebook or follow on Twitter and the weighted decisions we make that have budget implications.

Make 35,000 Better Decisions Each Day

Various internet sources estimate that an adult makes about 35,000 remotely conscious decisions each day [in contrast a child makes about 3,000] (Sahakian & Labuzetta, 2013). This number may sound absurd, but in fact, we make 226.7 decisions each day on just food alone according to researchers at Cornell University (Wansink and Sobal, 2007). As your level of responsibility increases, so does the smorgasbord of choices you are faced with.

You and I have been given a free-will and a multitude of choices in life about:

- what to eat

- what to wear

- what to purchase

- what we believe

- what jobs and career choices we will pursue

- how we vote

- who to spend our time with

- who we will date and marry

- what we say and how we say it

- whether or not we would like to have children

- what we will name our children

- who our children spend their time with

- what they will eat, etc.

Each choice carries certain consequences - good and bad. This ability to choose is an incredible and exciting power that we have each been entrusted with by our Creator and for which we have an obligation to be good stewards of.

Choices compound - we see this most evidently in the choices we make with our spending and the way they collectively impact the balance sheet. These accumulated choices all work together over a lifetime to take us to various outcomes. Individual choices that concern only ourselves – such as what to eat for lunch – will seemingly only impact us personally, as they pertain to the time they require, the cost, the impact to our taste buds, energy level and health, etc. However, a leader’s decisions always interact with others choices and actions. These leadership decisions create a ripple effect for spouses, families, teams, business units, organizations, communities, states, nations and even the world-at-large.

Decision-strategies, styles and inclinations direct your choices:

- Impulsiveness – Leverage the first option you are given and be done with it

- Compliance – Going with the most pleasing and popular option as it pertains to those impacted

- Delegating – Pushing decisions off to capable and trusted others

- Avoidance/Deflection – Either ignoring as many decisions as possible in an effort to avoid responsibility for their impact or just simply to prevent them from overwhelming you

- Balancing – Weighing the factors involved and then using them to render the best decision in the moment

- Prioritizing & Reflecting – Putting the most energy, thought and effort into those decisions that will have the greatest impact…and maximizing the time you have in which to make those decisions by consulting with others, considering the context, etc.

In all likelihood, we probably employ a combination of several of these decision-strategies in a situational manner in order to deal with the sheer volume of decisions we face. However, our approach to decision-making is the first critical choice we have.

Impulsiveness

Obviously, some of these decision-strategies are better utilized than others. Steven B. Sample was the 10th president of the University of Southern California, so he is certainly a man who knows a thing or two about making critical decisions. In his experience, the timing of a decision is critical. He relates that “…every subordinate knows that if he comes to the leader with a question and can get a quick decision, the chances are fairly high that the decision will be to the subordinate’s liking; after all, the subordinate will probably be the only person whom the leader will consult on the matter” (82).

If you trust the subordinate’s critical thinking and decision-making skills, then an impulsive decision may work not only in the subordinate’s favor, but also in your favor as the leader. However, impulsiveness can get us in a great deal of trouble because it does not allow for other inputs or for binary thinking (e.g. thinking through both or all sides and implications before rendering an opinion or decision). If we are too impulsive, we can actually decide before we think.

Compliance & Delegating

Compliance is also incredibly easy. It can also work in the political context where it pays to be popular. However, when it is regularly used, it is most often an indication of a leader lacking personal courage or much in the way of a constitution.

Delegating on the other hand is a critical style – especially as the numbers of decisions grow in the group or organizational context. However, trust must be established with those to whom you are delegating – especially as it relates to their follow-through, morals, shared values, intellectual horsepower, objectivity, interpersonal savvy, etc. Just because a leader delegates the decision-making power, it doesn’t mean they can absolve themselves of the responsibility for the implications- especially when a wrong decision is made.

Avoidance/Deflection

Avoidance or deflection of decisions can be thought of as a form of fatalism. Avoidance or deflection of essential decisions can also be fatal for the leader and their followers. “Sometimes no decision by Tuesday is in fact a decision by default. In other words, if failing to make a decision by next Tuesday means that the decision will be effectively removed from the leader’s hands by external forces or that his options will be significantly narrowed, he must have the courage to make a conscious decision by Tuesday and get on with it. For it is one thing for a leader to delegate a decision to a lieutenant, but an entirely different (and unacceptable) thing for him to surrender a decision to fate or to his adversaries” (Sample, 83).

However, there are also decisions that are seemingly inconsequential (e.g. Do I change the cable channel?) and an argument can be made that some of these are rightfully ignored, long-deferred or left to the input of others. And before you think yourself above this particular decision-strategy, consider the fact that some decisions just get missed in the flurry of the thousands we face. These overlooked decision opportunities would also be categorized here.

Balancing

Balancing can be an incredibly value-added habit and it is one often attributed to Benjamin Franklin. It requires the person to brainstorm, list and weigh both the positive and negative attributes and implications of the decision according to the desired outcomes they potentially lend themselves to. It becomes even more valuable when it leverages a Likert-styled scale of 1-7 to score each of the attributes listed according to how much they add or subtract value (e.g. +7 = a highly desirable attribute/implication and – 7 = a highly detestable attribute/implication). Pros and cons are then scored in summary to help determine best the final decision. This quantifiable approach helps the leader to think objectively and in binary fashion about the decision context. As a result, this style helps the leader see both sides of the decision ramifications. Of course there is simply not enough time to go through this exercise for the 35,000 decisions that we supposedly face each day.

Prioritizing & Reflecting

Prioritizing and reflecting requires the leader to evaluate the decisions they face. It reviews criteria that define the effort, resources and time involved in addressing the various decisions.

- Tier 4 decisions are decisions that can risk being deflected and thereby passed over without involvement or a response from the leader. In this case the leader never takes ownership of the decision, nor do they put any energy into delegating the decisions.

- Tier 3 decisions are decisions that typically have answers which are easily rendered and can risk being left to a simple impulsive or compliant response? These decisions can be routine decisions, decisions that don’t require much research, outside input or intellectual brain power, as well as decisions with implications that don’t carry a great deal of weight. Many times the confidence you have in the person bringing the decisions to you and the elaboration they provide can tell you whether or not it belongs here.

- Tier 2 decisions are decisions that either can OR need to be delegated to a trusted lieutenant that is closer to the situation, has more expertise on this context or that simply has more time and energy to devote to the context? These decisions clearly have implications that are potentially significant and they need attention from somebody with the combination of knowledge, follow-through and problem solving skills necessary to address them competently.

- Tier 1 decisions both need AND are best answered by some combination of the leader’s own expertise, consultation with subject-matter-experts and strategic thinking. When the balancing style is used here as a subset, the pros and cons are scored according to how well they advance or detract from the current mission and values of the person or organization that the decision will ultimately impact.

Values-based decisions

Values-based decisions significantly help us make better ethical choices, occupational-career choices, faith-related choices, political choices, and relational choices (Rokeach, 23). They can also help speed up our ability to make choices by way of helping us recognize the values preferences they contain (Rokeach, 23).

Researchers Verplanken and Holland found that individuals only made choices consistent with their values if those values were ‘cognitively activated’ (e.g. if they were conscious of their values in the decision context) (Parks & Russell, 677). The research reveals that when we make values-based decisions we tend to feel more positive about them and they can actually lend themselves to our ongoing motivation (Parks & Russell, 679). As such, a leader in the ranks of an organization with the shared values of scholarship, service and spiritual formation would do well to prioritize decision choices specific to how well they support and advance those values. Each person and organization has a different set of values that need to be leveraged in leadership decisions.

Tier 1 decisions are usually not decisions that you want to make when you are tired or at the end of a string of hard and involved decisions, where decision fatigue sets in. Research reveals that good decisions require ‘mental energy’ that gets depleted by repeated decision-making (among other things) and impacts decision objectivity and quality. In one study, prisoners who appeared early in the morning before a judge received parole about 70 percent of the time, while those who appeared before the same judge late in the day were paroled less than 10 percent of the time (Tierney, 2011).

Tier 1 decisions are the decisions that a leader wants to devote appropriate amounts of time to. President Harry Truman personified this trait. “Whenever a staff member would come to him with a problem or opportunity requiring a presidential decision, the first thing Truman would ask was, ‘How much time do I have?’….Truman well understood that the timing of a decision could be as important as the decision itself. A long lead time opened the door for extensive consultation and discussion; a very short lead time meant the president could only look inside his own soul, and then only briefly, for an answer that might affect millions of people” (Sample, 81).

Your most critical decisions don't just impact your circumstances and the circumstances of others. Your most critical Tier 1 decisions are the primary shapers of your character. For instance, when you face disappointments and trials in life, your response dictates the character that will be created in you as a result. If your tendency is to have a pity party, then you'll be some combination of pitiful and pathetic. If you get resentful or angry on a level that leads to a pre-occupation with mechanisms of self-protection or vengeance, then you'll either become withdrawn, vindictive, bitter or hardened-of-heart. If you ignore these occurrences or attribute them to random luck, you'll become ignorant and apathetic.

However, if you learn from them and release them (by way of things like taking responsibility, showing forgiveness to yourself and others, pursuing thankfulness and understanding), you will be wise, humble, and tender-hearted. And in this last case, your disappointments and trials can actually lend to a better version of you (rather than a lesser version). As a leader, your character is what will either endear or repel you from others.

As decisions become more complex and more pertinent to either shaping character or the fulfillment of the mission and values of the leader or organization, they progress in Tier level. When we face Tier 1 decisions, we need to pray and invite God’s input and direction. Divine input is the primary source of competitive advantage for the Christian leader making difficult and future-defining decisions. After all, an omnipresent and omniscient God has a line of sight to things that a finite leader does not. Christian leaders have access to God’s input via scripture, prayerful meditation/reflection, Divine intervention as revealed in circumstances and the counsel of Godly people.

7 key habits to keep in mind when making decisions:

- Prioritize your decisions and be sure to give appropriate amounts of time, research, reflection, consultation and energy to the Tier 1 choices before you. Amidst 35,000 potential decisions, our ability to prioritize the significance of the decision context is our first important decision;

- Constantly be developing a group of folks that you can delegate decisions to. If you want to be an increasingly effective leader and a promotable candidate, you WILL need to develop a trusted group of decision-makers that you can delegate to and count on to follow-through. Give them a line of sight to how you make decisions so that they can learn from it and leverage it;

- Develop a ‘think tank’ of trusted-truth-tellers, subject-matter-experts and people who have a proven track record of decision quality so that you can run key decisions by them;

- Print out your own personal core values and the shared values of the organization you are presently leading in for reference when facing decisions. This simple act will help you make better values-based decisions;

- Practice! Play games that require you to make decisions in a relatively safe and playful context. Playing board games, card games and computer based games can be fun and they have also been shown to improve your ability to make better decisions and come to the right conclusions according to David Gamon, Ph.D., coauthor of Brain Building Games. Practice may not make you perfect, but it will greatly improve your decision quality. Sites like Luminosity.com also help people capitalize on this research and the opportunities it presents to gain this valuable practice;

- Keep a piece of paper available with a line drawn down the center. Develop your own Likert-styled scoring system of 1-5 or 1-7 or 1-10 (e.g. 1=minimally lends to my values vs. 10 = maximizes the realization of my values). Positive attributes get positive scores. Negative attributes get appropriate negative scores. Attributes that are neutral score zero. Use this process to develop your binary thinking skills and to score potential decision options – their pros and cons;

- Make sure you learn from your bad decisions. You want the price you pay for any bad decisions that you make to be the insightful learning that is gained, rather than the regretful days of depression you inflicted as a result of self-loathing. Ask: What would you do differently next time? How can this experience make you better? Self-loathing is a seriously over-rated recovery mechanism that emerging leaders just don’t have time for.

In conclusion, if we want to make better decisions as leaders, we would do well to remember that our decisions impact others and compound over time. Some decisions carry more weight on the outcomes we generate than others. As a result, they should be elevated when determining the decision-strategy we will use, as well as in the resources of time, talent and energy we devote to them. The decision-strategy we use will likely dictate the outcome, so it needs to be our first decision when we step up to the choice buffet (yes, we even have a choice about how we make a choice).

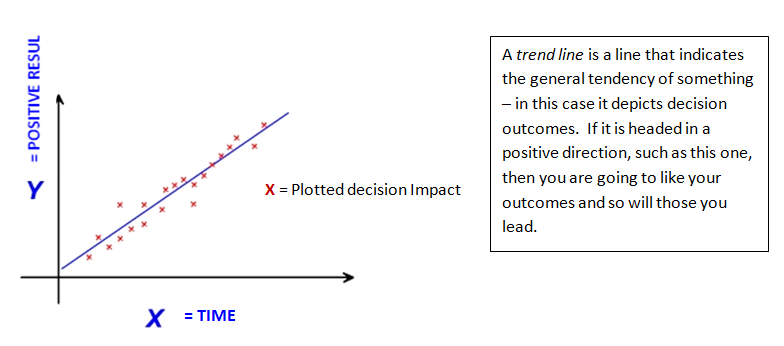

Our decisions as leaders have the potential to all collectively work together in taking us to some pretty significant places in life. Over time they will create positive or negative trend lines for us, as well as for our organizations (see the illustration above). The good decisions can take us to the heights of heaven....and the bad decisions can take us to some very dark times and places. We need to celebrate the good decisions and the outcomes they lead us to, because what gets celebrated is more likely to get repeated.

Are you getting better outcomes as a result of the decisions you are making about who to hire, who to date, who to promote, what to eat, what to invest in, etc.? Well then, that is worth some additionally positive self-talk, a pat on the back from your free hand or someone significant….and maybe even a Café Zorro at a nearby Starbucks. On the other hand, if as one internet source reported, we come to regret a decision as we do 143,262 of the choices we make over our lifetime (Hazell, K. J., 2011); we need to learn from our mistakes, so we don’t repeat these bad decisions…and potentially subject others to them.

As Christian leaders we need to thank God for His redemptive power over the bad choices we make, as well as for His ability to ultimately cause even these seeming misses and ‘goose eggs’ to grow us. In a world where time is linear, we cannot go back and undo the past. This is why the concept of forgiveness is so brilliantly critical in dealing with the past. While bad choices contain negative consequences, we can recover from them in the context of grace and we can help others recover too. It is fair to expect improvement from ourselves and others, but it is not fair to expect perfection. Lastly, we also need to thank God for the wisdom He gives us so that we can make good choices more often than not. In the end we come to the realization that effective strategic leaders create meaning through their decisions. They realize that their best decisions are just a reflection of their values in action.

Joel Hoomans is Assistant Professor of Management and Leadership Studies at Roberts Wesleyan College as well as Director of Graduate Studies in the Division of Business. He holds a Doctorate in Strategic Leadership from Regent University. Prior to his involvement at Roberts Wesleyan College, Joel worked for Wegmans—the premier grocery retailer in the United States—as a human resources professional, eventually becoming their first Manager of Leadership Development. Learn more about Joel.

Joel Hoomans is Assistant Professor of Management and Leadership Studies at Roberts Wesleyan College as well as Director of Graduate Studies in the Division of Business. He holds a Doctorate in Strategic Leadership from Regent University. Prior to his involvement at Roberts Wesleyan College, Joel worked for Wegmans—the premier grocery retailer in the United States—as a human resources professional, eventually becoming their first Manager of Leadership Development. Learn more about Joel.

Additional Reading

- Time Lords & Lackeys: 3 Timely Habits of Great Leaders by Dr. Joel Hoomans

- Focus, Finish, Celebrate: Keys to Strategic Leadership by Mike Bargmann

- Altruistic Leaders Put the Team Ahead of the Task by Karen Benjamin

References

- Hazell, K. J. (2011, April 11). How to be a better decision maker. Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2011/11/14/how-to-be-a-better-decision-maker_n_1091959.html

- Parks, L. & Guay, R. (2009). Personality, values and motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 675-684.

- Rokeach, M. (1979). Understanding human values: Individual and societal. New York: The Free Press.

- Sahakian, B. J. & Labuzetta, J. N. (2013). Bad moves: how decision making goes

wrong, and the ethics of smart drugs. London: Oxford University Press. - Sample, S. B. (2002). The contrarian’s guide to leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Tierney, J. (2011, August 11). Do you suffer from decision fatigue? The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/21/magazine/do-you-suffer-from-decision-fatigue.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

- Wansink, B. & Sobal, J. (2007). Mindless eating: The 200 daily food decisions we overlook. Environment and Behavior, 39:1, 106-123.